- Home

- Alex Segura

Silent City Page 2

Silent City Read online

Page 2

Pete seemed to recall the bartender, Jesus, being generous last night. Most of the evening was clinked glasses, slurred conversation, and a foolish drive back home on Biscayne Boulevard to his Little Haiti apartment. His usual nighttime ritual of three glasses of water and four Advil—plus whatever seemed edible in the fridge—had done little to prevent this anguish. Pete wasn’t even sure if he’d managed to get one glass down before passing out.

Before he could decide whether he would get up or try to finagle an extra hour of sleep before work, Pete heard the familiar pounding on his door. It was Costello, his four-year-old black cat, alerting him that, yes, it was time for breakfast, hangover or not. Costello had become very methodical in his requests for food. Thump. Thump. Tortured meow. Thump. Thump. Questioning meow. It was cat jazz, Pete thought, and then laughed out loud. Yeah, he was still drunk.

His dry mouth and all-over ache made it clear to Pete that he wasn’t getting up just yet. This didn’t deter Costello, who Pete had named after Elvis—not Lou—during a particularly obsessive period that had never really disappeared. The case of records near his desk could attest to that. The only Costello albums collecting dust were recent stuff. And “Goodbye, Cruel World,” too. He leaned over, found an errant shoe, tossed it at the door. The racket stopped. For now.

Pete fell back into bed, trying to block out the sunlight by closing his eyes and letting his mind wander. Bits and pieces from the night before flooded back, between the throbbing of his headache and his aching body. He remembered talking to Mike Carver, one of his few remaining friends since he’d returned to Miami, after a stint as a sports reporter in New Jersey had gone up in flames, and drunkenly thanking him. For what? Pete wasn’t sure. There was a girl, too, at some point. He hadn’t gone home with her, as he was in his own apartment. Pete groaned again. Every time he awoke like this—feeling like shit, hazy on what he’d said or done the night before and usually embarrassed by what little he did remember—he’d promise himself it’d be the last time. So far that hadn’t worked. He rolled over in bed, facing the wall. He could still sneak in an hour or two of sleep before he had to head to the Miami Times newsroom. Back to the grind of his life now. Copy editing the stories he used to be tasked with writing. A paper pusher in a time when paper—and newspapers—were dying.

Then the phone rang.

Pete rolled back and reached for his cell phone, which was blaring a scratchy, digitized version of the Replacements’ “Waitress in the Sky” as its ringtone. Great song, Pete thought, but not now. The sloppy, shuffling delivery Westerberg gave the ode to flight attendants wasn’t what Pete needed. The sad, pleading lyrics only reminded Pete about how sad and pleading he’d been the night before. The alarm clock’s red numbers taunted him as he checked his phone. It was Mike. He wondered what kind of details he’d find to fill the gaping holes in the memories from last night.

“Yo.” Pete half coughed his first word of the day.

“You still asleep, bro?” Mike let “bro” drag out for a few extra seconds, an old college joke that wasn’t funny anymore but had become a habit. Pete could hear that Mike was on the road, probably heading back to his apartment up in Fort Lauderdale from his girlfriend Tracy’s house. Mike, like Pete, had been pretty tanked in the wee hours of the morning. Unlike Pete, though, Mike knew when to stop.

“Nah, I’ve been up for a while,” Pete lied. “Have fun last night?”

“It was good. Good to see the crew. Too many shots, though,” Mike said. “How’d you get home? You were still with that chick when I left.”

“Which chick?” Pete asked, instantly regretting it. Shit. What chick?

Mike laughed. “Never mind. I didn’t know who she was. It seemed like you guys knew each other, though.”

Pete thought back. He remembered the girl now. Stephanie—a former co-worker from Pete’s time in Jersey. She was also friends with Emily Blanco, formerly Sprague, also formerly Pete’s fiancée. After the breakup, Emily had done a stint as a designer with the Miami Times before settling down with her new husband, Rick, down in Homestead. Pete liked to think they were friends now, in that weird, stunted way people tried to be friends with someone that broke their heart. He liked to think that, at least. Pete grimaced. Stephanie was in town covering the Miami Book Fair and just happened to be at the same joint where Mike, Pete, and a few other friends were imbibing: Kleinman’s, a narrow sports bar nestled in a half-empty condo building just a block away from the Times. Pete only got back bits and pieces of conversation, but he could see Stephanie’s face. A sad, pitiful look. Not for her, but for him. Maybe it was better that he didn’t recall what they talked about.

“You’re lucky you just had to drive a few blocks, bro. D-U-I…” Mike sang the dreaded three letters.

He was right. Pete had been stupid last night, could barely remember anything after that last shot of schnapps. Not anything clear, at least. But being such a creature of habit helped. Pete could stumble home pretty capably from anywhere. Or so he told himself. What was the term for this—”Functional alcoholic”? Best not to think about that.

“Yeah, I remember now,” Pete said. “She was a friend of Emily’s from Jersey. I don’t really remember what we talked about. I’m sure she’ll tell Emily all about how wasted her almost-husband was. Great.”

“Eh, fuck it. I wouldn’t worry about it too much,” Mike said. “Who cares what Emily or her idiot friends think?”

Mike was always good for this kind of support. He was a coworker and a good friend. Always loyal, always forgiving, he helped Pete come to terms with his own failings. Or at least ignore them. Pete wondered if this would all be easier if Emily had stayed in New Jersey, allowing Pete to create this idea of her in his mind as an evil person, so he would not have to cross paths with her regularly, only to be reminded of why he fell in love with her in the first place.

“Anything going on tonight?” Pete asked, more out of habit than anything else. The last thing he wanted was another drink. But he was kidding himself if he thought he wouldn’t have one or two before the day was done.

“You nuts? Nothing, man. I’m just going to chill at home,” Mike said. “I need to do some shit around the house.”

“Yeah, I should do the same,” Pete said. He gave his bedroom a quick once-over. “You work tonight?”

“Nah, I’m off. Unless Vance calls me in. That dick.” Mike laughed at his own profanity. “Alright, I’m out. I’ll talk to you later.” Click.

The abrupt ending to the call, much like the beginning, didn’t faze Pete. It’s how he and Mike communicated.

He returned to bed, eyes on the ceiling. Headache was better, Pete thought. He couldn’t help thinking of Emily, and he groaned aloud at the thought of what Stephanie—a girl he’d met once at a random dinner party—would tell her about their encounter. Knowing Emily, though, she’d never mention it to Pete. She’d made it clear that she was no longer going to try to fix him. It wasn’t her responsibility anymore.

After a few minutes, he dozed. In that cloud between sleep and wake, Pete found himself dreaming. He was younger, probably in high school. He was riding shotgun in his dad’s old blue Ford Fairmont, down 87th Avenue, in Westchester, the Miami suburb that young Pete had called home. He was smiling. The sun was out. The leather seats of the car felt hot on his arms and his back. His father had the oldies station on. The Beatles were playing, Pete thought. “Hey Jude”? His dad was wearing his usual short-sleeved business shirt, tie, slacks, and thick glasses. He was still working. A homicide detective for the Miami PD. He looked good, healthy. He was smiling, too. It was summer in Miami and all was good. A leggy Dominican girl crossed the street in front of them and Pete saw his father motion with his chin. “Esta rica, no?” Isn’t she lovely? Pete shrugged and looked out his passenger side window. In his dream, he wasn’t sure why he did that. His father looked away. Pete could tell his disinterest hurt his father. The dream fizzled. Pete awoke sad. His cat had gone quiet.

Ch

apter Two

Pete’s battered black Toyota Celica wheezed its way up into the Times’ main parking garage. While working nights at the paper allowed him to sleep off the most brutal of hangovers, it never guaranteed a parking space. The broiled meat smell wafting from the McDonald’s bag resting next to Pete in the passenger seat made him wretch a bit. Too soon for a double cheeseburger and fries.

After some swerving around, Pete snagged a space on the garage’s top floor, open to the elements, which meant his car would still be a sauna when his shift ended, around midnight. Summers in Miami were brutal. A tropical paradise most of the year, Miami became unbearable from late May until about mid-September. For Pete, who wasn’t much of a beach guy, that meant a lot of time indoors, in cars, and in bars. Pete winced. Sweat was already through his black polo.

He stepped out of his car, snatched the Times ID badge hanging from his rearview mirror, and collected his grub. He sighed as he walked toward the Times building, nestled between a vacant strip mall and the expressway.

• • •

The newsroom was in its early stages of life. People were still shuffling in for the evening shift, and the unluckies forced to work weekends were already gone, desperate for some semblance of a normal schedule. Pete nodded here and there as he made his way across the Features cubicles toward Sports, where Pete found his desk in the same shape he’d left it two days prior—disorganized and funky. He tossed his food to the side, sat down, and logged on. Pete had the dubious role of “duty officer” on weekends, meaning he had to represent the Times’ sports section at the nightly news meeting and oversee the pages being sent to press throughout the night. It also meant Pete had to come in at least 30 minutes earlier than usual to familiarize himself with what was going on in the sports world. His hangover and junk food run had eaten into any chance for prep. Pete was barely on time.

He hadn’t bothered to listen to the sports talk stations on his way in, nor had he scanned the wire last night—too busy moaning into his toilet bowl. He began to unpack his dinner-for-breakfast as he waited for his archaic computer to boot up.

To say he wasn’t in good standing with his bosses was an understatement. Pete had eliminated whatever reputation he’d built up as a basketball beat writer for the Bergen Light in his first few months at the Times. He was consistently late, mediocre when he was actually working and, while pleasant to be around, not terribly interested in his work. Pete knew this. He did little to change it. He found the job of copy editor boring. The drudgery made his last job—covering Jersey’s pro hoops team—seem like a vacation, even though by the time he’d gotten that gig he was already spinning his wheels. He had his reputation to thank for this job, though. A few years out of college, Pete had used keen sourcing and a knack for analyzing records to uncover a small-scale gambling operation involving the assistant basketball coaches at Hamilton University. The story vaulted Pete from small-town-general-assignment reporter to hotshot sports writer. That’s when things got fuzzy, Pete remembered. Instead of being picky and waiting for the right job to come around, he’d jumped at the first chance he got to cover a big-league team, and that was his undoing. The travel, hotels, hotel bars, and expense accounts mixed a little too well with his thirst for drink, and soon he found himself unhappy, almost married, and in a cold-weather state that lacked the appeal and draw of New York.

Then his father died.

That’s what brought Pete—and at the time, Emily—back to Miami. The plan was to stay for a few months and get his father’s affairs in order. His mother had died in childbirth and Pete was the only son of Pedro Fernandez Sr., respected and retired Miami homicide detective. Pete had no choice. Three months had turned into a year. The Bergen Light refused to give him any more paid leave, Emily had left him, and he’d settled for an editing job when he had previously been one of the nation’s rising writing stars. The full scope of Pete’s career collapse was still just an abstract idea in his head most of the time, but days like today, when the mundane reality of his new life stared right back at him, he felt a great sense of loss -—and really wanted a drink. Pete’s screen flickered to life in yellow on black.

• • •

Pete barely noticed Chaz Bentley walk into the newsroom. It was well past 11, and he was putting the finishing touches on a late Marlins game recap while looking over a proof for an inside page. Pete, despite his general disregard for his duties, was proud of his headline writing and took some pleasure in making sure there was something there that would pull a reader in. The page was already covered in red marks from its first pass through the copy desk, and Pete envisioned a few more rounds before the night was through. As on most nights, Pete had his headphones on, trying to drown out the usual newsroom din as he focused on the words and sentences forming on his screen and on the pages the printer spat out with alarming frequency. Pete had a Pixies mix going, the opening, deceptively melodic bassline of “Debaser” pulsing into his ears, when he felt the tap on his shoulder at the moment the song kicked into sonic apocalypse. Pete took off his headphones and wheeled around to face Chaz Bentley, the Times’ local news columnist. In his early sixties and inching toward retirement, Chaz was one of the guys that had been around forever, worked every job and inhaled every part of the city. At least that’s what the Times brass wanted readers to think. Pete didn’t buy it. Chaz had seen better days. He was kept on the payroll mainly for his name—which still seemed to rate with the huge senior citizen readership. In reality, Chaz barely wrote more than his required weekly puff piece, and even that was a product of heavy editing and lots of hand-holding. Pete felt sorry for him. He’d only spoken to him a handful of times in person. It was odd for a columnist to be in the newsroom at this hour, unless there was an urgent rewrite needed. Why he was in the Sports area was doubly baffling.

“Hey, uh, you got a sec?” Chaz was rubbing his hands together. Pete looked across the room. The clock was ticking. The paper was inching close to the deadline for the final edition.

Chaz looked around the newsroom. Everyone seemed deep in his or her respective tasks. The loud bustle of a few hours ago had been replaced by a hum.

“Sure,” Pete said. “But I’m a few minutes from deadline and I’ve got three stories in my basket. Did your column get shifted to one of us by accident?”

“No, no, nothing like that,” Chaz said. “I—uh—look, I know this may sound strange,” he trailed off. He could smell whiskey on Chaz’s breath. A glance back at his monitor indicated a growing number of messages blinking at Pete from colleagues across the newsroom. More than half of the messages were probably screaming “WHERE ARE MY PAGES?” Pete slid his hand through his short dark-brown hair and leaned back, eyebrows raised.

“Well, I think Kathy’s missing.”

“Kathy?”

“Yeah, my daughter,” Chaz paused again. Pete thought back. Kathy. The news reporter. She was friends with Emily. They’d bonded soon after Emily had returned to Miami with Pete and had done a stint as a designer for the news desk when it was clear they were not going back to New Jersey. They’d all hung out together a handful of times. Kathy was pretty, blonde, thin, and relatively friendly the few times Pete had spoken to her. Flirted with her was more likely. He’d considered asking her out a few times, but never could find the right moment. It also didn’t help she was friends with his ex.

“Missing? What do you mean?” This time Pete made his glance at the clock obvious to Chaz. I am late now, he thought. In a few minutes, Steve Vance would be calling to see why the pages hadn’t been released to the plating area, where they were then put on the actual presses. Pete knew that was the last call Vance wanted to make on his day off, close to midnight.

“Listen, can we meet up and talk about this?” Chaz said, his face now sleek with sweat. “I just need a few minutes of your time.”

“Sure, sure.” Anything to get back to work, Pete thought. If he hurried, he might avoid the Vance call and get the pages out under the gun. They’d

be full of errors, but they’d be done. “Just let me know when. I’m free tomorrow.”

“No, it has to be tonight.”

“Where?”

“Do you know the Abbey?”

“Yeah, yeah. Hole in the wall on Alton?”

“Yes,” Chaz said, his voice clearer and in control now. “Near the beach. Next to the McDonald’s.”

“I should be out of here close to one. That too late?”

“No. Let’s meet there at a quarter to two. That work?”

“Sure. See you then.”

Chaz walked off. Pete turned back to his monitor. He had felt the stares from his fellow sports editors, stuck waiting on him, as he chatted. Pete tried not to think about how odd it would be to sit with Chaz, who was around the age his father would be if he’d lived, at a bar at two in the morning, no less. Pete tried to focus on work. There were still a few late West Coast baseball games tonight. The scores wouldn’t be in for at least an hour, if then. He’d have to blow them off to meet with Chaz. The website guys could post them, Pete thought.

Despite his lingering hangover, the idea of another drink appealed to Pete. It had taken Pete a minute to even make the connection between Chaz and Kathy. Kathy, the investigative reporter all the editors lusted after. Daughter of the surly “columnist” who never dared show his face in the newsroom unless he had to. Something was really weird.

Still, there was work to be done. Pete pushed Kathy, Chaz, and everything else to the back of his mind and dove into the pile of proofs and e-mails that had converged around and inside his computer, the clock taunting him. Had the sports team—or, better said, Pete—managed his time better, the final section would be more complete. He said a silent prayer in the hope that he wouldn’t hear about this tomorrow. Sometimes it worked. The newsroom bustle filled his ears, the faint sounds of the Pixies’ “U-Mass” tinny from the headphones he’d set aside, Black Francis yelling “It’s educational!” as the newspaper skidded toward deadline.

Bad Beat

Bad Beat Miami Midnight

Miami Midnight Dangerous Ends

Dangerous Ends Down the Darkest Street

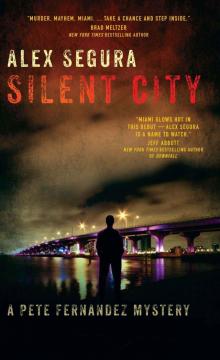

Down the Darkest Street Silent City

Silent City